This article was originally published in La Nación Magazine on Sunday, May 22

By Alejandra Ocampo

Around mid XIX Century, the British cavalry officers who served in India were captivated by a sport which was played by the nobles of the subcontinent, which was also known as the “Crown Jewel of the British Empire”: it was called polo. Those British officials brought polo to the West on their return to England, via Malta; but the way the sport was played a bit messy in India, the British decided to provide the game with an appropiate set of rules, a number of four players per team and established the Hurlingham Polo Association as the governing body of polo, with the first tournaments played under their rules. Shortly, the sport was discovered by the Americans; not only they were as enthusiastic about it as their English counterparts but they also became their most tough contenders.

In addition, the Americans gave polo the final touch, by creating the handicap system to rate each player between 1 and 10 goals. And of course, the first ever 10-goaler in history was an American, Foxhall Keene, who not only was a brave polo player but also an extraordinary sportsman.

In the meantime, Argentina was receiving a large number of inmigrants, who came from a devastated Europe; people who were looking forward to settle in a safe, prosperous and rich country, politically established and with a wonderful future ahead. Among those inmigrants were the British, who chose to settle in the countryside, mostly in farms, known as estancias, in the Province of Santa Fe. In addition, they brought some interesting news, such as various sports – football, rugby, tennis, polo. The latter ended up being a favourite pastime for both the estancieros and their grooms, named criollos or gauchos, whose extraordinary skills as horse riders left the British in awe.

These grooms used to ride without a saddle, and seized the reins with one hand to play a sport named pato (duck), which required enormous skills and ability. After seeing this, the British decided to teach how to play polo to these brave grooms, to whom the horse had no secrets at all. Moreover, these grooms learned incredibly quickly. Shortly, Santa Fe would become a very important centre of polo, while the sport started to spread in the different estancias all over Argentina, and the first clubs started to emerge. The registers mark that the first polo match ever played on Argentine soil took place on August 30, 1875. Campo vs. Ciudad (Countryside vs. City) played that day in a place called Estancia Negrete, set in a village called Ranchos (today General Paz), in the Province of Buenos Aires, and owned by a British sheep breeder, David Shennan.

Several of those British who settled in Argentina used to travel to their country, to play the polo season. One of them was Hugh Scott-Robson who, in 1896, made a tour of England with a team representing Buenos Aires Polo Club. Considered the first big polo star of Argentina, Hugh Scott-Robson was born in 1878 in the Province of Entre Ríos, and was educated in Scotland. He’s been a remarkable, strong ambidextrous player, who played as a back, and one of the founding members of the Hurlingham Club, in Argentina, in 1888. Scott-Robson was joined by Newman Smith, Frank Furber and R. McC. Smiyth for the 1896 tour of England. There are no further details about the games, but it is known that there were very good reviews about the horse string they brought.

In 1897, another team representing Argentina made a successful tour of England. The lineup, composed by Francis Balfour, John Ravenscroft, Frank White and John Porteus, all of them pioneers of the sport in Argentina, won 17 out of the 23 games they played. But the real stars of the tour were the horses, all of them exclusively Argentine bred. The remarkable performance of these horses left the British in awe. By late XIX Century, early XX Century, the first Argentine players started to travel to England, with the aim to learn and get experience. Finally, in 1912, Argentina would have the opportunity to make their most important tour of England up-to-date; the tour would set the path for the ultimate international recognition for Argentine polo ten years later.

A Scotsman in San Luis

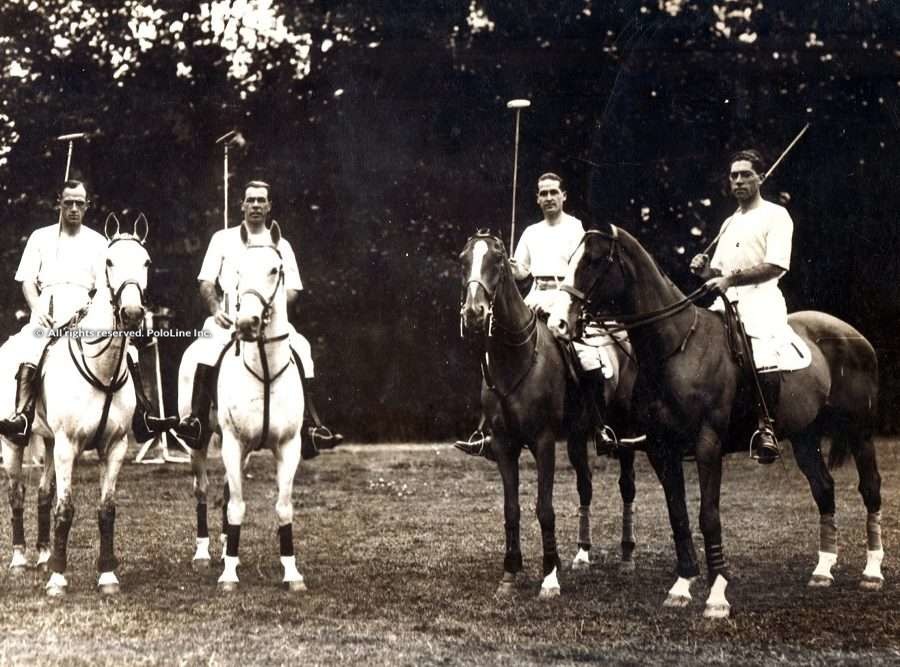

Harold Schwind (1873-1922) was another of the big British pioneers of polo in Argentina. Born in Edinburgh, Schwind arrived to Argentina at 21, and owned an estancia in the Province of San Luis, named El Bagual, with livestock as the main activity. Schwind, who used to travel to Europe on a regular basis, decided to organise a tour in 1912, with a team named after his estancia. He paid all expenses and provided 22 horses from his own string. El Bagual Polo Team, rated at a handicap of 22, was composed by Schwind, John and Joseph Traill – both from the estancias Las Rosas and Las Limpias, in Santa Fe – and Leonard Lynch-Staunton, as well as a substitute, John Campbell. The son of Scottish parents, Campbell was the only player of the team born in Argentina, in 1877, in a village called Flores, back then a countryside area in Buenos Aires. He was a gifted and very well mounted player. El Bagual went to England with the aim to keep learning and acquire more experience.

But their aim largely exceded their expectations. The tour of England was a walk in the park for El Bagual, reaching the final of the Whitney Cup, after winning all their league games against First Life Guards, Wasps and Old Cantabs. The powerful 32-goal Eaton foursome and their extraordinary horse string, perhaps the best in England, were waiting in the championship match. And to everybody’s surprise, Eaton, who received 11 goals on handicap, lost to El Bagual 21-11. El Bagual’s remarkable performance earned rave reviews in England and they became the sensation of the season in London. Even The Polo Times wrote “the brilliant Argentine players”. Campbell, the substitute, played that final subbing in for the injured Lynch-Staunton, and he scored four goals. It is worth noting that these players were known in Argentina as English, Scottish or Irish, while in their home country they were Argentinians. The Duke of Westminster, the patron of Eaton, impressed by the performance of the Argentine horses, decided to buy many of them for his own string.

El Bagual’s remarkable success, then, set the path to what would come ten years later.

But before, the world had to face the most extreme, tough challenge: the First World War, known also as the Great War, the first big international armed conflict of the XX Century, that would last between 1914 and 1918 and which not only introduced a new form of war, the terrible air raids, but also ruined Europe and life completely on every aspect. Due to his sense of duty John Campbell joined as a volunteer. This was remarked in a letter he wrote to Lewis Lacey, on August 4, 1914: “I’ve just heard that war is declared between England and Germany. Although possibly it may seem foolish, I would prefer not to play public polo, while our people is at it over there; so I hope you will allow me to stand out (…), we shouldn’t be here but should be on the way to the other side”. Campbell would never return from the war: he died on December 1917, due to the wounds sustained in the battle of Cambrai.

Like Campbell, a significant number of British officers, pioneers of polo both in England and Argentina, went to the war as volunteers or summoned by their country. And like Campbell, many of them never came back. The appalling war lowered considerably the number of those enthusiastic British officers, polo players and pioneers of the modern sport.

The time of accomplishment

Once the war was finished, life began to settle down slowly, and polo came back to the grounds. And while Argentine polo was hugely praised, England and the United States still remained the sport’s most powerful countries. In 1886, they started to play against each other in a competition named The Westchester Cup, considered the oldest international trophy in polo history, that presented the winners with a massive silver Cup, designed by the prestigious American luxury jewelry and specialty retailer, Tiffany’s.

In 1882, the British pioneers founded the first ever governing body of polo in Argentina, The Polo Association of the River Plate. But in 1921, with polo spreading rapidly all over Argentina, another governing body was created under the name of Federación Argentina de Polo with Joseph Monroe Hinds as Chairman. “The wish to send an Argentine team to England to play the tournaments over there, led to the idea to create another governing body in order to have an official representation”, wrote Francisco Ceballos, Vice President of the Federación Argentina de Polo, in the first part of his book El Polo Argentino (1969, Comando en Jefe del Ejército, Comando y Dirección General de Remonta y Veterinaria). Ceballos also stated that the Federación was established because not only the British played polo but also “many latin names and local players were coming up to the sport, with the same aims as the British. Their contribution brought new blood, as well as bravery and passionate interest”.

The brand new governing body decided to send a strong team to England, with expenses in charge of the Jockey Club and a contribution from the Federation as well. A total of eight players made the trip: the main team composed by Lewis Lacey, David Miles, Juan Miles and Juan Nelson, and a “B” team made up by Luis Nelson, Eduardo Grahame Paul, Alfredo Peña Unzué and Carlos Uranga. “The selection of the horses (…) was crucial and thanks to some friends’ priceless contribution (…) we were able to complete the string, with the exception of those of Alfredo Peña, who already had them in England. The horses departed from Buenos Aires in February 1922. José Hemmings, a seasoned trainer, who was provided to us by Mr. Martínez de Hoz, was in charge of the horses”, said Juan Nelson, member of the 1922 main team, in the second part of Ceballos’ book.

The arrival of the Argentine team in London was quiet; Peña greeted them with everything perfectly organised for the horses, players and grooms, which, according to Juan Nelson, “was a great relief”. The Argentine team settled in Neasden, near London, where they played practices and gave a look to the teams they were to play against. In May, they went to Hurlingham, in London, to leave the horses there, and on May 10, the main foursome, played their first practice against Templeton, at the Ranelagh Club. The visitors claimed an impresive 9-2 win.

In their second match, Argentina surprised everybody with a heavy 11-2 victory against no less than the Freeboters, the legendary Walter Buckmaster’s team. However, they didn’t do well in the following tournament, the Social Clubs Cup, at Hurlingham; the Argentine team was dropped in the first round. But the loss was an advantage for them, because they left them with enough time to prepare for the next one, the Whitney Cup; indeed, the same cup El Bagual won ten years before.

Argentina swept Eastcott and Cowdray to secure a spot in the final of the Whitney Cup and would battle against Quidnucs for the title. They won 8-5 and claimed the second Whitney Cup for Argentina. Next they won the Roehampton Club Open, and they finished their tour of England with the highlight of the season, the British Open, at Hurlingham. In semifinals they defeated the Freeboters once again, and went on to play the championship against Eastcott (– Stephen Sandford, Earle Hopping, Vivian Lockett and Belgium-born player, Alfred Grisar), on a very cloudy July 1 1922, that expected rains, “a storm that caught us in the third chukka (…); the heavy rainfall turned the game into a true water-polo, which didn’t favoured our quick game, but indeed revealed us as first class players”, Nelson remembered. The water-polo ended up with Argentina victorious 12-8, which meant that Argentina claimed their first British Open in history so far.

A British journalist wrote about this remarkable achievement the famous quote “They have put Argentine on the map”. They were still celebrating the victory when they received a cable from Louis Stoddart, the President of the United States Polo Association (USPA). Stoddart was so impressed about what Argentina did in England that he invited them to play the US Open. In their arrival to the US, they were greeted like heroes by a significant number of media, directives and fans.

The horses, all of them in perfect conditions, arrived previously, and were were settled in New Jersey, at Rumson Country Club, where the tournament would be held. It is worth noting that the US Open was played at Meadowbrook, in Old Westbury, New York, but in 1922, they decided to move it to Rumson. “The grounds were splendid, but different to the British, which were very dumped due to their deep and humid grass; the grounds in New Jersey were light and quite the same as ours”, said Nelson.

The first thing the Argentine players did in the US was to watch a game at Piping Rock Club, in Long Island, with Louis Stoddart. They played their first practice on American soil a few days later against a anglo-american lineup; the Argentine team won the six chukka practice by a 8-7 score. Everything was ready for the next step: the US Open.

The Argentine lineup for the US Open was exactly the same who won the British Open – Lewis Lacey, David Miles, Juan Miles and Juan Nelson. They defeated Shelbourne by a 12-6 score in semifinals to meet the poweful Meadowbrook in the championship match, a team that had two of the best American players in history, Tommy Hitchcock and Devereux Milburn, who were joined by F. Skiddy Von Stade and Elliot C. Bacon. On September 10 1922, the fully packed grandsstands at Rumson Country Club were expectant to see the local team and the heroes of the British Open; the first ever 10-goaler in history, Foxhall Keene, was among the spectators.

Argentina and Meadowbrook played a very intense and hard fought game, and by half time, Argentina had a 6-4 lead. But a very scary moment came up at the start of the fourth chukka: a clash and a heavy fall that involved David Miles and Devereux Milburn caused Miles a serious tear. The contest was stopped to watch after the injured player, who was apparently not able to go on. But Miles refused to leave the battle. Said Nelson: “(…) it was necessary to cut the boot and put a very tight bandage (…) and add a tennis shoe provided by a spectator. He insisted to keep playing, in front of the enthusiastic crowd. As a result of the accident, he was not able to play for three weeks”.

Miles’ bravery was stronger than any injuty. “As temperamental as he was, he quickly produced four consecutive goals”, remembered Nelson. Four crucial goals, to claim the second achievement. Argentina defeated Meadobrook 14-7 and claimed the US Open.

The pupils learned from their teachers; the historic 1922 tour set the path to what continues today. And who’s better to provide an accurate definition than the worldwide and renowned polo historian, Horace Laffaye (1935-2021). In his book “El Polo Internacional Argentino” (1989), he wrote: “No other team has claimed the British Open and the US Open in the same year and with the same lineup. But what’s more important is that the gentlemen who represented our polo left a legacy of sportsmanship and nobility which will be a role model for all the generations of polo players to come in Argentina”.

Finally, and as a consequence to this remarkable achievement, on September 14 1922, the River Plate Polo Association and the Federación Argentina de Polo merged to set the Argentine Polo Association. A hundred years of history, a hundred years of the best polo in the world.